Canada is a huge market that great international brands such as Bacardí or Captain Morgan have already conquered. When you know that the Quebec monopoly, the SAQ (Société des Alcools du Québec) is the first buyer of French wines in the world, you could think of it as a small El Dorado for rum producers.

But small producers, especially French ones, have more difficulty to impose themselves there, notably because of restrictions concerning the ethyl carbamate naturally present in ‘agricole’ rums, and the system of monopolies that governs the sale of alcohol in the different provinces. But things are moving in the right direction!

Canada has always had a tumultuous relationship with alcohol in general, and especially with spirits. It’s almost like they have a love-hate relationship. In 18th century, it appeared that love had triumphed. In 1769, the first distillery in Quebec was founded.

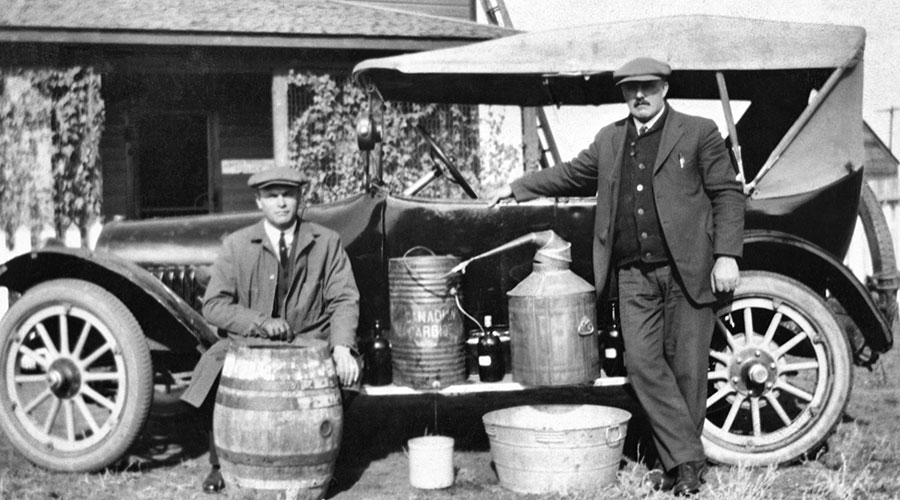

It produced rum by importing molasses since sugar cane does not grow in these latitudes. Very quickly, the colonists turned to grain spirits, which did not pose a problem in terms of raw material supply, and the first Canadian whisky was born in 1799. The success of spirits only increased and there were more than 200 distilleries at the end of the 19th century. But this success caused troubles, people drank too much and a movement advocating temperance developed and, after, prohibition.

In 1878, the ‘Scott Act’ gave the right to municipalities to ban alcohol from their territory. In 1901, an entire province, Prince Edward Island, went into prohibition. From love to hate. Numerous movements were formed with the goal of closing down drinking establishments and preventing alcohol consumption (for social, religious, sanitary, and moral reasons).

In 1918, Prohibition was finally imposed. However, it was possible to consume alcohol while declaring to be ill, which gave rise to numerous frauds! The problems linked to the unreasonable consumption of alcohol decreased, but smuggling exploded, as it did in the United States, which also adopted its own prohibition law in 1920 (until 1933). As early as 1919, Quebec rejected prohibition, followed over the years by the other Canadian provinces (until Prince Edward Island, again, abandoned it in 1948).

Because of its long border with the United States, Canada became the preferred route for smugglers wishing to smuggle alcohol into Uncle Sam’s country.

The establishment of monopolies

However, at the beginning of the 1920s, a system began to be set up that would last until today. Each province created a monopoly (in Quebec it was the Liquor Commission in 1921) which authorized the sale and consumption of alcohol but strictly controlled the circuit.

From then on, the only references that could be purchased were those that had been approved by the monopoly. Better, or worse, alcohol lovers must now buy in the state stores… of their province. You can’t go shopping in the next province! “This rule was recently relaxed,” says Marc-André Gagnon, journalist and founder of the website vinquebec.com, “and now you can go and buy a few bottles in other provinces, but it is forbidden to resell them to your friends.”

Why go looking for bottles elsewhere? Because each province has its own catalog and does not distribute the same products. In addition, a private individual is not allowed to buy rum on the Internet unless it is on the website of their monopoly, or even at the independent wine shop, if it is not listed.

However, rum enthusiasts have a lot to do because there are nearly 200 references available in Quebec alone… and yet, given the excitement that currently affects the world of rum, with brands being born every week, this appears to be very little.

The major challenge for rum producers is thus to get listed by powerful monopolies such as the Société des Alcools du Québec (SAQ, a distant descendant of the Liquor Commission) or the LCBO in Ontario.

The role of agents

Easier said than done. There was a need for a profession that would act as an intermediary between monopolies and brands, so agents were born and developed. “95% of the products referenced at the SAQ are found and defended by agents,” says Annie Des Groseillers, Strategic Consultant for Wine & Spirits/Expertise Rum.

The agents become the eyes and voice of the producers. For example, they are the ones who will try to convince the powerful SAQ to distribute the brands they have in their portfolio, and then they will take their pilgrim’s staff to try to convince the different stores (more than 400 at the SAQ alone) to sell them.

Because, even if the SAQ imposes a portion of what its stores will sell to individuals and professionals, the latter’s managers have some flexibility in selecting from among the available references.

“Be careful, you have to choose your agent or association of agents carefully, you have to check if there are not too many similar products in your catalog to avoid cannibalization and, if you have a very specialized product, it might be better to turn to a smaller agency to avoid getting lost among hundreds of brands.”

advises Annie Des Groseillers. “And no matter how well known or how big the agency is, there is no certainty or guarantee that the product will make it to the SAQ or LCBO.” Especially if the product in question contains ethyl carbamate!

Damn carbamate!

It is this molecule, which appears during fermentation (and remains after distillation), that causes a slew of problems for agricultural rum producers. We read on the Canadian government’s website that it is considered ‘as a substance with worrying effects on human health’.

If the Scotch Whisky industry has taken measures since the 1980s to avoid the appearance of ethyl carbamate (by selecting special barley varieties) and that molasses rum is only slightly affected by the phenomenon, it is not the case of agricultural rum, particularly prone to the appearance of ethyl carbamate (cane juice containing a number of cyanogenic glycosides).

To enter the Canadian market, producers of ‘agricole’ rum (but also cachaça and other rums made from pure cane juice), have to make heavy investments to change the fermentation process, the varieties of cane, the distillation equipment… “There was too much ethyl carbamate in the Martinique rums that I used to buy from,” says Cédric Brément, founder of Ced rums.

So I had to create a completely new recipe distributed only in Quebec that contained rum from Guadeloupe, less affected by the problem. Even if all of the rules are followed, the process is lengthy and uncertain, and many brands that have sent their bottles to Quebec or Ontario must ship them back after a few months because the monopoly’s analysis labs have declared them non-compliant. “”Due to the Covid 19 crisis, product requests have been delayed, and some references are running out in SAQ stores,”” says Annie Des Groseillers.

“We have presented two new products that have received a first validation, but it has been eight months since we have had any news…”, confirms Cédric Brément.

A market yet to be conquered

But despite the obstacles, rums from France and elsewhere are holding out because they know that “the market is lucrative and that the SAQ and LCBO are known as good payers,” explains Marc-André Gagnon (see our interview with Simon Bourbeau, Account Director, Supply Management at SAQ).

This is how ‘agricole’ rum brands such as Trois Rivières, Saint-James, Branca (Madeira) and more recently A 1710, have managed to establish themselves. As well as rums from Haiti like Barbancourt, Casimir, Sajous, Vaval or Communal. At SAQ, however, we find mostly molasses rums of Spanish and English style, with brands like Bacardí or Captain Morgan taking the lion’s share.

But there are also more and more Quebec and Canadian rums. “The rums from here have not suffered the logistical problems caused by the covid crisis and have thus filled the gaps,” explains Annie Des Groseillers. “But this is also due to the quality of brands like Rosemont in Quebec or Leatherback in Ontario and the fact that the SAQ is looking for local products.” At the LCBO, Canadian rums are even the most represented origin, with 30 references out of about 120.

On the French side, there is one reference at Saint-James and another at Plantation (but the rum comes from elsewhere). The market is still to be conquered. This will not be easy because, even if the Quebecers seem to be open to the discovery of atypical products (for them) that are French rums, the English-speaking Canadians are more cautious (see our report on ‘agricole’ rum for export in September 2020).

Monopoly and monopoly

Canada is divided into 10 provinces of varying size and population (from 161,000 in Prince Edward Island to 14.5 million in Ontario): Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Saskatchewan.

While all Canadian provinces have a monopoly, not all operate in the same way. For example, Alberta has a monopoly that manages the importation of products but not their distribution, which is left to the individual.

A product entered at the SAQ will almost automatically be renewed year after year, which is not the case at the LCBO, which is stricter. In the USA, several states also have monopolies, including Pennsylvania, as in Europe with Sweden, Finland and Norway for example.