The Daiquiri Cocktail, made with Cuban rum, sugar and lime, is one of the three main rum cocktails, along with the ‘Ti’-Punch’, made with cane juice rum, sugar and lime, and the ‘Caïpirinha’, which is made with cachaça, sugar and lime…Recipes are similar.

It is difficult to know for certain the circumstances surrounding the birth of the Daiquiri Cocktail. However, many agree on its creator, Jennings Stockton Cox, and its birthplace, the iron mines of Daiquiri in Cuba.

The American engineer, who came to Daiquiri following the American-Spanish war of 1898, established a Bacardi ration for the workers in the iron mines. Later, using ingredients available to him, he experimented with different blends to finally produce a Daiquiri.

Another version comes from Jennings Cox’s granddaughter. She relates that this cocktail was invented when Cox received American guests. He had no more gin and did not want to offer a dry rum, so he made a cocktail with ingredients he had. And the Daiquiri was born…

Whatever its origins, Jennings Cox recorded the recipe in his logbook. It is a recipe for six people (possibly Cox’s American guests?) and uses the following ingredients: juice of six lemons, 6 teaspoons of sugar, 6 Bacardi cups of ‘Carta Blanca’, 2 small cups of mineral water, plenty of crushed ice. Shake well.

This new cocktail remained within Cuba for some years, because at the same time, in 1900, the Cuba Libre cocktail (rum, lime, Coca-Cola) was created and became immediately famous. The little town of Daiquiri was also hit by a plague epidemic in 1903.

All this changed in 1909. The ship USS Minnesota was in Cuba and the captain, Charles H. Harlows, suggested to medical officer, Lucius W. Johnson, to visit different places of the American-Cuban War. They stopped in the town of Daiquiri where a battle had occurred. Jennings Cox was still there and served them a Daiquiri cocktail. Lucius Johnson took the recipe back to the ‘Army and Navy Club’. This private club, which still exists today, was created in 1855, following the American-Mexican War. In 1950, Lucius Johnson related his memory to the Baltimore Sun newspaper: ‘He mixed in each glass a jigger of rum, the juice of half a lime, and a teaspoonful of sugar. He then filled the glass with finely shaved ice and stirred it well. In that hot, humid weather the ice melted rapidly and the glass quickly became frosted. We were delighted with the drink…

The club boasts a Daiquiri room in honour of the battle. Tradition says that the cocktail is drunk here, in front of a painting of the ‘Santiago Bay’.

Some internet articles attribute the diffusion of this cocktail to the Navy. However, this does not seem probable since alcohol is forbidden on board vessels—although the Daiquiri cocktail would certainly be enjoyed by sailors in a wider context.

Johnson introduced the cocktail to the Baltimore University Club where the barman added bitter to the recipe. This recipe has been passed down through the years, and is today proposed as a variation of the Daiquiri cocktail, although in the Army and Navy Club, it is served without bitter.

During the 1910s, the cocktail was served in some bars. The Astor Hotel bar, one of the most prestigious hotels of New York, served it in 1914. It was described in the New York Tribune as “a sort of rum cocktail much favoured by persons who have lived in the tropics”. The barman explained that he served a dozen or two a day, to ‘boys from the Navy yard’.

In 1916, an American-German chemist, Karl Grueneklee, established a plantation in Cuba to produce a concentrated lime juice. This lime was made to be carried in the pocket. One of the unique selling points of his juice was the opportunity to make a Daiquiri whenever you wanted: ‘there is as fine a Daiquiri cocktail as anyone could want’.

But the Daiquiri had to wait until the prohibition period in the USA to become famous, with tourists and barmen flying to Cuba to drink alcohol.

The Bacardi Rum was the first brand of rum to be advertised. It was promoted on walls across the USA with the slogan: ‘Cuba is great. There is a reason: Bacardi.’

Bartenders’ books gradually started to include Daiquiri Cocktail recipes. The ‘Savoy Cocktail Book’ published in 1930, proposes a recipe similar to Jenning Cox’s recipe, although it proposes a variation with lemon, probably because it was difficult to find lime at this time. An extract of Joseph Hergesheimer’s book is published with a recipe. The presentation begins with this sentence: ‘The moment had arrived for a Daiquiri. It was a delicate compound; it elevated my contentment to an even higher pitch’.

Some books, like ‘Cuban Cookery’ published in 1931, remind us of the origins of the cocktail: ‘while the Guantanamo Naval Station was being established, in the early days of the Republic, a group of officers were initiated into the secret of a cocktail made with the juice of green limes and Bacardi rum. It was immediately named Daiquiri, in honour of its birthplace, a little mining town nearby.’

The ‘Gentleman’s Companion’, published in 1939, presents Harr E. Stout as co-creator of the cocktail, with Jennings Cox.

And the ‘Cocktails, their Kicks and Side-Kicks’ invents a history….the Daiquiri would be created by soldiers during the American-Spanish war to complete the beef and onion ration…

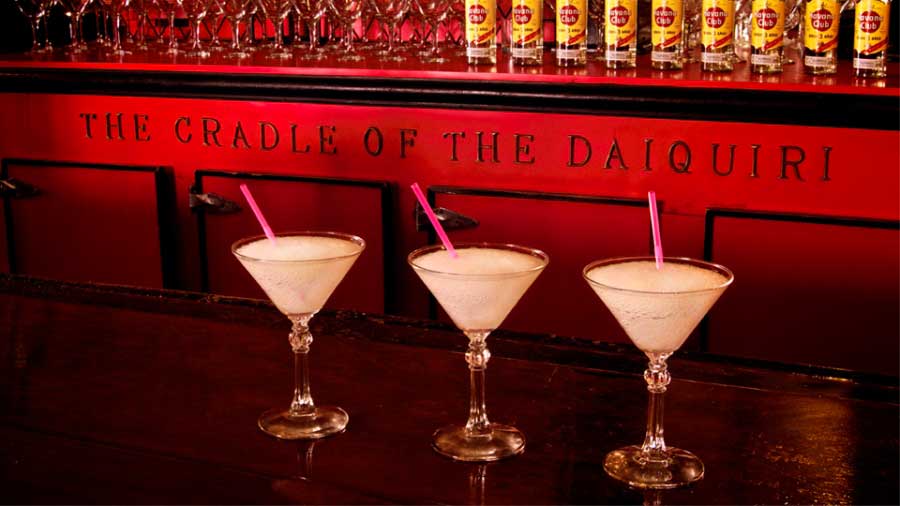

In 1934, the Cuban bar, ‘The Florida’, which became ‘The Floridita’, and was also nicknamed ‘the Cocktails Cathedral’, presented a book with four variations of Daiquiri. In 1939, this bar was presented as ‘the Cradle of the Daiquiri Cocktail’ and proposed five variations of cocktail. The bar claimed to make 10 million Daiquiri…

The technique of one famous barman, Constante Ribalugua, to whom is attributed many variations in 1915, resided in the use of the lemon. The lemon was pressed by hand to extract the juice without extracting the bitter oil contained within the peel.

The success of this cocktail was so important, that a special rum was created: the ‘Ron Daiquiri Coctelera’ by the ‘Compania Ron Daiquiri S.A.’.

In 1938, the Daiquiri appeared in a French mixology book, ‘Cocktails’ by Jean Lupoiu. In France, it is mentioned in some articles towards the end of 1920s in some short fiction. In 1936, we red a big article in the Figaro about the American presence in Cuba. Daiquiri was presented as the most famous cocktail, along with the ‘El Presidente’ and the ‘Mary Pickford’.

After the Second World War, David Embury writes about Daiquiri, in his mixology books: ‘Why more Daiquiris are not sold: the use of inferior rums and the use of improper proportions’. For example, he highlights that the Cuban practice coming from Havana bars, like the ‘Florida’, and ‘Sloppy Joe’s’ imposed a variation with pineapple, whilst the ‘Sevilla’, the ‘El Patio’ and the ‘The Hôtel Nacional Bar’, used inferior quality rums from Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Lemon was also used more than lime as it was cheaper than lime and it started to be overused in cocktails.

We also find in the 1935 ‘Old Waldorf-Astoria Book’, the cocktail book of the eponymous hotel, advice about the use of the ice: ‘The order of adding ingredients is important. Personal preference dictates serving the cocktail with finely shaved ice in the glass’.

The influence of bartenders was of paramount importance for the posterity of the cocktail. The Daiquiri was promoted by bartenders, as opposed to grog, for example, which was mainly promoted by the medical sector. The work on the recipe goes on.

Jeff Berry, nicknamed ‘Jeff Beachbum Berry’ is the owner of a tiki bar in New Orleans.

Amy C. Collins and Claire Bangser reported on his technique, in an article published in punchdrink.com. He claims that to make a good Daiquiri, you must not to use sugar syrup as this unbalances the citrus taste from the lime, but rather you should dissolve the sugar in the lime juice. For this, Berry uses a blend of four parts white sugar to one part demerara sugar.

For the rum, Berry chooses to use an alcohol content in keeping with the drink’s origins. Today, Bacardi Carta Blanca, recommended by J. Cox, is 75-overproof, but Berry thinks that this same rum was originally 89-overproof. He therefore uses an overproof rum of 86 or 89 to try to replicate the original taste. And if you want to mention ice, Berry needed 18 months to find the perfect Daiquiri taste which he serves today to his clients!

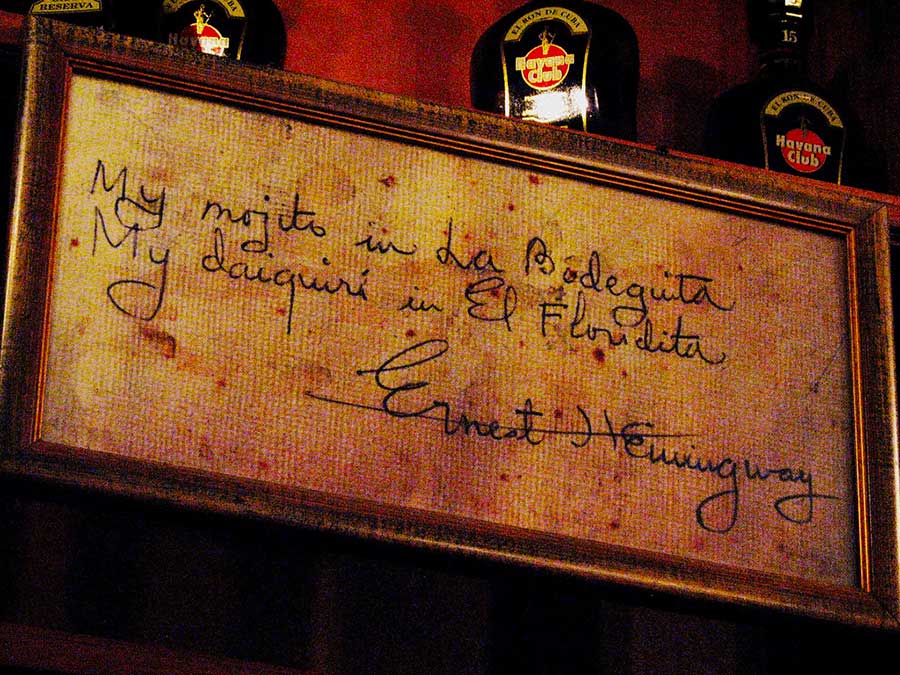

We cannot finish this article without speaking of a man who was very important for the notoriety of this cocktail: E. Hemingway. The writer came to Havana in 1928. A big drinker, he was nicknamed ‘Papa Dobles’ due to the double Daiquiris he drank in the ‘Florida Bar’. A cocktail, the ‘E. Hemingway Special’, was created in his name, with grapefruit and maraschino cherries.

Thank you to:

Yoann Demeersseman

Elizabeth Bowes

Bibliography:

Difford, Simon, La Bible des Cocktails, Hachette Livre, Paris, 2013

S. Lott, Arnold, J. McHugh, Raymond, A History of the Army and Navy Club, The Army and Navy Club, Washington, 1988

Website: