Here, we are no longer witnessing the Marc Sassier of Saint James rums, Martinique, a true rum expert with a technical, historic and strictly regulatory approach: a real Occam’s razor! He has agreed to respond to us, but in a personal capacity, since in addition to his role as director of production at Saint James, he also presides over the Sugar and Sugarcane Technical Centre (CTCS) and the tasting jury for the AOC, in charge of registered designation of origin in Martinique.

Rumporter: Marc, in your opinion, when is a rum no longer a rum?

Marc Sassier: This sugarcane spirit, which is sometimes given the name Cachaça or, more generically Arrack, depending on the area of production, is defined in Europe by the regulation 100/2008. Behind the name lie several approaches and definitions; there is not one rum but several rums. Whilst it is generally accepted that its origin is linked to sugarcane or molasses derived from sugar production, other countries have a larger definition, so some add characteristics such as aromas (see the national law in Guatemala COGUANOR NGO 33011, for example) whilst others open up the scope of possibilities (Indian definition 2012, point 2.5, which authorises beetroot as a base ingredient but forbids any artificial colouring!)

So, as a minimum, rum should be produced exclusively from sugarcane juice or molasses, as stated in European legislation. This poses an issue of clarity for the consumer, regarding what she or he is consuming in terms of both the content and the labelling of the container, that’s my personal opinion.

IN TERMS OF THE RUM

By keeping the base material as sugarcane, a dichotomy is created between “rhum agricole” and “industrial rum, or rum”. From there, the fermentation process influences the aromatic potential of the base material by modifying it, bringing it out, or transforming it, sometimes creating unique products such as the Grand Arôme. The distillation stage reveals this aromatic potential since, whilst the influence of the base material is still residual (so no notes of burnt sugar in “agricole”), the degree of distillation and the set-up of the still will have a large influence. In terms of the strength of distillation, you can get a light rum distilled at a high strength where the non-alcohol rate is currently hardly above 5g per hectolitre of pure alcohol, compared with a Rhum Agricole with registered designation of origin in Martinique, for example, at between 65 and 75%, with at least 225g of non-alcohol per hectolitre of pure alcohol. This rhum, which cannot be subjected to extraction/pasteurisation, successive columns and re-distillation, maintains its initial potential and hence all its variety.

It is also a question of historic use, in “rhum traditionnel” with French Geographical Indication, this high minimum rate of non-alcohol was a response aimed at impeding the market dominance of wine spirits following the mildew and phylloxera crises. This was a time when those of the English-speaking world, particularly to get away from the taste of rum, used multiple distillation and created an alcohol which was as neutral as possible (extra-pure!), especially at the end of the 19th Century with the search for absolute alcohol. Hence the French criteria for rum could be said to be for it to have organoleptic characteristics (since 1903). When it reaches the point where rum lightened to the maximum becomes a base that one then flavours in order to sell under the title of rum… is the base material not enough in itself? To each their own art of production… (see the edition of Rumporter dedicated to distillation).

IN TERMS OF THE FINISH, ADDITIONS

There is of course rum “de coulage”, made from a variety of possible combinations in terms of base material (fresh juice, heated juice, syrup, molasses…), fermentation processes (controlled temperature, bacterial temperature, yeast temperature…), distillation processes (column, multiple distillation, with or without extraction…) which opens up a world of possibilities. This again gives the producer a lot of room to manoeuvre. Leave it light or wood age it? But then what kind of wood? Large casks or small barrels? What variety? What temperature? Previous contents? And this is where personal strategies are used to reveal its unique character compared with another. The problem is not the possible combinations but what lies beneath this, the ability to see the forest for the trees. And, I would recommend reading the books about counterfeit spirits from the beginning of the 1900s up to 1920, where you will find a more or less similar debate to the one being had today. In my opinion, the unique character of the rum should be the driving force behind its conception.

For example, a woody aroma has been authorised since the decree of 1921 in France, however it is only mentioned in the 110/2008 regulation for wine spirits. In technical terms, a water-based wood extract is added to the spirit to make up for extraction from the casks, thus allowing old casks to be used, which provide many advantages, especially an economic one considering the current price of casks on a market faced with a lack of supply. If the wood is oak, and the extract is water-based and not from another process, as is the case with rum, should any aromatisation be detectable? I don’t think so, as long as controlled practice is maintained (i.e. degree of obscuration) because the door shouldn’t be opened to the use of wood left, right and centre in order to compensate for industrial production methods, stainless steel vats, for example. Likewise, shavings do not reflect proper usage with natural aging; they could have undergone heating, as well as flavourings which are not necessarily safe.

Likewise, when one talks about the “finish”, what does that tell us: a cask chosen to introduce natural aromas in a specific way or a commercial addition to help sell the product and create an air of newness whilst creating new limits, even if there is a risk of having a product which has ceased to be a rum and has become swallowed up by the added product? Texts on this subject in France and at a European level (art. 103 of the EC 1308/2013) state that a mix of two categories produced with or without geographic designation create a “spirit drink” and the rule includes categories of mixing, compound names and their labelling (INCO and 110/2008).

The addition of sugar is part of the same debate, should sugar be added to correct an imbalance, to add to the body or make the product taste appealing when it is not enough on its own as is? Here, again, Europe has defined them as punches or liqueurs but has also defined categories of sugar or caramel (which is part of the same debate) which are very different: colorant, sweetener. But in the words of a friend “is this not creating a false debate which indirectly assumes that sugar is necessary, and therefore already accepted?”

A simple way is to limit obscuration or masking (difference between the real strength in alcohol and the strength measured by density) using these additions, since by changing the density the strength is lowered (hence the term obscuration or masking of real strength), particularly using sugar in an almost linear fashion. So for 1% of masking, between 3 and 4g of sucrose/litre is needed, however for rhum vieux, interactions with wood extracts must also be considered. And the masking of such additions adds up. In rhum with registered designation of origin in Martinique (without additions) obscuration increases with age, reaching its maximum after 15 years without ever having surpassed 2 degrees. Hence the degree of obscuration, which is simple to measure, remains a good marker for a natural spirit versus an “improved” one, whether this is through wood extracts, sugar or any other ingredient, this should therefore be limited. If some bodies such as the GI and A.O.C have done it, why can’t the others?

In current times, where rum is also distinguished by its origins, how can this not be rendered obsolete by the addition of sugar, which flattens any intrinsic difference in the product due to its base material and process? How can we talk about rhum agricole which excludes any derivative from sugar production when there is a desire to drown it in this ingredient? It is curious to hear talk of adding sugar without ever hearing about the limits or the influence on the product, as if this should be and indeed is something natural. It is therefore worthwhile to consider the effect of sugar on the final taste in order to know if this affects the notion of origin; imagine a chocolate whose origin was decided based on its amount of sugar!

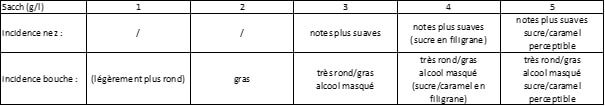

So I personally tested this with a 3 year-old old classic to which I added sugarcane sucrose and I noted the change in both the aromas and the masking (or obscuration) linked to the sugar. Then I added the same sucrose to rhum agricole to see what effect this had on the taste of the product.

It was noticeable that the sugar quickly modified the texture and then the aromatic element and that above 5g/l the product is clearly modified. So how can we be sure of the origin or characteristic of a product as a difference whilst tolerating this ingredient, since it is not the rum which makes the product but the sugar? And how can we justify doing this when we try to medically reduce the amount of sugar in edible commodities, which spirit drinks are a part of?

TO CONCLUDE

In conclusion, in my personal opinion, it is clear that rum is growing in popularity and everyone, from the most longstanding producers to novices, wants to play a part in this interesting area. But at what price and for how long? The stakes are enormous, both financially and in terms of modifying the existing product. So what should we expect of a rum? The moon? Would we ask a wine to not be a wine? … Because this is the stage we are at, where in order to differentiate themselves some are fighting the established norms. Do the parameters not set out that the process should be used to find niches without using additions which do not make it rum but turn it away from its true nature? In the end, is it necessary to sacrifice the specificities of origin and process to join the majority? And is this not abandoning one’s trade, one’s art, for a simple bargain? And then what will be left when all these fashions, all these conformists, have passed?

Let’s not make an enemy of legislation, which is responsible for all evolution and diversity… like in the times of pirates! In short, let’s not attribute our losses and our mercantilism to it, but let’s keep it as our safeguard. Is the current success of French geographic denominations, which spark the interest of other countries, not the sign of expertise which has made a name for itself through rigorous and controlled definition which guarantees its nature? And does the current passion for “agricole” not rely on this rigor, which is what sets the product apart? But it is not enough to merely define principles, they must also be respected and applied to protect the consumer, and be shown through regulated labelling, consumers have the right to know what they are consuming!

This is not contrary to diversity; we do not want to reverse roles in order to destroy what exists. Hence nothing prevents a brand from developing a new product which, if it proves to be good enough, will have no need to use the terminology “rum” or the associated geographic designation in order to be a commercial success. Likewise, whilst rum is a major ingredient of mixology, it must remain so and be defended as it is now, but not all mixology should become “rum”! I believe that changes should focus on the success of the product which is called “rum” as it has been known throughout its history, which is clearly defined, not a product named ‘rum’ just because someone or another wants it to be.