Although his impressive title of ‘global rum ambassador’ was self-appointed, Ian Burrel has truly become one of the most respected authorities in the world of rum over the decades. An ambassador for the category, author, creator of new blends and brands, and inveterate traveller, this Jamaican based in the United Kingdom shares his vision of rum and reflects on the Equiano affair.

How did you become interested in rum?

First of all, I am Jamaican. I learned to love rum at a very early age because it is part of my culture, it’s in my blood. Then, professionally, one of my first jobs was as a bartender. So, naturally, I specialised in rum-based cocktails. That’s how I got involved in rum, through my work.

And when did you decide to work in the rum industry?

A bit by accident. I was a bartender in London, but I was also doing lots of other things. I worked in radio, television, played professional basketball, and also made music. I was constantly busy. And then I had the opportunity to do an advert for Appleton Jamaica Rum in the mid-1990s. I met with the decision-makers at J. Wray & Nephew, and they offered me a part-time job as a brand ambassador. They didn’t have one in the UK at the time, so I was the first. That’s how I got started in the rum industry.

And now, how would you define your job?

It’s difficult to describe my job, but I am the global ambassador for rum. It’s a title and a job I gave myself! And it stuck. Over the years, companies in the industry have come to respect what I’ve accomplished and have truly recognised me as an ambassador for their category. So today, my official job is to promote the rum category.

Every category? Molasses rum as well as agricultural rum, English rum, Spanish rum and French rum?

All rums. And it goes even further than the rum category strictly speaking; my work now extends to all sugar cane spirits. For example, I went to Mexico last week and learned more about charanda, which has its own appellation in Mexico. It’s a bit like cachaça in Brazil, viche in Colombia, or clairin in Haiti. So I’m learning more and more about the different types of sugar cane spirits, which means I have to travel all over the world to be able to talk about them, rather than relying on a Google document.

Let’s get back to rum. How do you explain it to people who know nothing about it?

That’s a good question. I always start with two definitions. The first definition is what rum officially is: a distillate of fermented sugar cane juice, syrup or molasses. This broad definition allows me to connect with people wherever they are. Whether you’re in India, Jamaica, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Cuba or North America, rum is an intrinsic part of the local culture with a particular vision. So I always use that definition too. The second definition is that rum is the spirit of culture and historical heritage. Rum has an official definition. But it also has a cultural definition. It is defined differently in many countries according to local customs.

You have been working in the rum industry for over 30 years. What major changes have you seen?

For me, the biggest changes have been in understanding what rum is, particularly through the stories told about it, marketing, and how it is promoted. When I started out in the 1990s, rum was just white, amber and brown. There were no nuances. In England, no one knew what agricultural rum was. So, from there to knowing that there is a difference between rums from Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion or French Guiana… As a Jamaican, I didn’t even know that rum was made in Barbados! So, understanding of different lifestyles around the world has come a long way in recent years. The other big change is the development of the premium and super-premium sector. So much so that today, people give rum the respect it deserves. It hasn’t been without its problems. There are also charlatans who have tried to ride the wave with what I call fake rums. For example, some companies use false age statements to make customers believe they are buying older rums.

Is rum destined to become a luxury product, like certain cognacs or whiskies?

Yes, many companies are playing the luxury card. All those that focus solely on super-premium rums are growing. This part of the market is expanding. In many countries, wealth is increasing, as is disposable income. COVID has also “helped” because people have had time to taste, try and understand more expensive drinks at home.

Aren’t these primarily marketing products?

Once again, marketing is one of the driving forces behind the growth of rum. It’s a bit of a double-edged sword. You can use it to promote generous, authentic things, but you can also use it for things that aren’t so good. Marketing is about getting people to buy. They try the product, and if they like it, they’ll continue to drink it; if not, they won’t buy it again.

What do you think of the current trend towards regulation around rum? The development of Geographical Indications (GIs), in particular?

I think it’s a very important thing. For me, for companies in the sector that are looking to take care of their brand, which is their territory, their country and the way they produce their rum. Rum is produced in so many different countries around the world! However, it does not comply with international rules, as there are no international rules for whisky or brandy for that matter. When you make rum in Jamaica, it is different from rum in Barbados, different from rum in Martinique, different from rum in Cuba… And I think it’s intrinsically valid when a rum takes its heritage, its geography, and packages it in a bottle. It means that the consumer knows what they’re drinking, that there’s transparency. They know where the rum comes from. They can assume that they’re dealing with a particular style of rum. Whether they like it or not, for that matter. For example, I love Irish whiskey. I’ve never tasted one that I didn’t like. On the other hand, I’m not a big fan of Islay whiskies.

You don’t like peat?

I appreciate it, but I’m not going to sit down and enjoy a glass by the fire either. But back to my point. If I buy a bottle of Islay whisky, I know it will probably be peaty and smoky. I know it’s a minimum of three years old. If it says 12 years old on the label, that’s the youngest drop in the blend. So, because of the geography, the rules, the regulations, the appellation, the brand, the GI… I know what kind of whisky it’s going to be. And that’s all I would like for rum. When people see a rum from Jamaica or a rum from Martinique in a bottle, they have a preconceived idea of what it is. Now, if there is no GI, anything can happen. For me, it’s transparency, quality and consistency that are important. And from a cultural point of view, it’s that the money and value go back to the country that makes the product. Because it’s the colonial model to take products from poor countries, bring them to a richer country where they are sold, without the value going back to the country of origin.

Do the raw materials for rum have to come from the country of production?

Good question. Let me use whisky as an example again. Most of the grain used comes from Scotland, but also from England and other European countries. But when the Scots buy this grain from elsewhere, they know how to transform it into a superb liquid. If you look at Switzerland, I don’t know where the metal for watches or chocolate comes from, but it’s not from Switzerland. So what matters is the know-how, the way rum has been produced for generations in a given place. Then, if your molasses comes from the country or, even better, from the estate, you can say so loud and clear, mark it on the label, for example with the words “single estate”. For example, Worthy Park in Jamaica can put “single estate” on its products. Customers are assured of traceability and are willing to pay the price. This does not mean that if you buy your molasses from another country, your products are inferior. However, it does mean more work for the marketing department.

And what about ageing?

It must be done 100% at home, in the country of origin. Let’s take the example of a Jamaican white rum that is aged for 20 years in England, say in Liverpool because I’m a supporter of the football club. Is it Jamaican or English? I would say English. But that doesn’t mean the rum won’t be delicious!

How important is traceability in the development of rum?

It’s very important. We live in a world where people want authenticity and traceability; they want to understand where things come from. The more regulations there are to show where products come from and how they are made, the better. As statistics show, people are drinking less but better. So, if you drink better, you need to know that you are drinking something authentic. And this doesn’t just apply to rum. I’ve just come back from Mexico, where there’s a big movement in favour of traceability in tequila. Normally, the raw material is 100% blue agave, with no additives, but you can find products that are 51% agave and 49% other raw materials and added sugar.

What do you think about adding sugar to rum?

I’ve always liked to say that there are good rums with added sugar and bad rums without added sugar. However, I think the European standard is too high, at 20 grams per litre. But at least it’s a step in the right direction. A few years ago, some rums arrived in Europe with so much sugar in them that they should have been classified as liqueurs. That said, I believe that if you want to be seen as a world-class spirit, there should be little or no added sugar in your product. On the other hand, if sugar is added, even a little, it must appear on the label. Always this requirement for transparency. I know it seems hypocritical when people say, ‘Oh, I want to know how much sugar is in it because I want to drink healthily.’ I say, ‘Alcohol is poison!’ So, if you want to drink healthily, drink little, drink well, and always have a glass of water nearby.

This brings us back to the issue of GIs, doesn’t it?

In European GIs and in certain countries, it is illegal to add sugar. Authentic Jamaican rum must not contain any added sugar. And that’s where transparency comes in, and that’s where the value of GIs lies, because it would set this rule in stone. But it depends on the country and its traditions. In Venezuela, for example, sugar can be added to rum.

How important is sustainable development for the future of rum? Will people buy rum because it is organic or Bonsucro certified?

Rum companies have realised that they really need to preserve and protect their country and their land. There has been some marketing and greenwashing, but we are seeing more and more sustainable practices in the rum industry. Sugar cane is increasingly sourced locally rather than imported. Distilleries are increasingly powered by renewable energy, such as solar power. Tidal and wave energy can also be used, as rum-producing countries are often surrounded or bordered by the sea. Many people would say that rum is probably one of the greenest spirits around. Second-hand barrels are used. Bagasse and vinasse are used to feed the soil, or goats, turkeys… food from the earth. Roberto Serrallés (from Don Q in Puerto Rico), who is probably one of the world’s leaders in biochemistry, has created a technique that makes vinasse clean and drinkable. It’s absolutely incredible.

And now, a few questions about the British market. What kind of rum is drunk in Britain?

We have a very strong connection with rums from the former British colonies. Rums from Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana… That’s why rum culture hasn’t really evolved in this country yet. The tradition of agricultural rum and ti punch hasn’t really broken through the cultural barrier. But when it comes to rums made from molasses using pot stills, they are very popular here. There are now fewer than 60 distilleries producing rum in the United Kingdom using imported molasses. Naturally, they cannot work with cane juice because it has to be fresh. There are a few companies that say they use dehydrated cane juice… but I think I’ll wait a few years before tasting it.

Would you say that knowledge of rum is growing in Britain?

Yes, knowledge of rum is growing. This is largely thanks to my festival, which celebrates its 19th anniversary on 11, 12 and 13 October. It is the longest-running rum festival in the world. I have influenced rum festivals in Paris, Germany and the USA, all over the world, and have often helped to organise them. As I said, when people came to my first fair in 2007, for them rum was either white, amber or brown. But now people are asking for rums from all over the world: Jamaica, Barbados, Venezuela, Guyana…

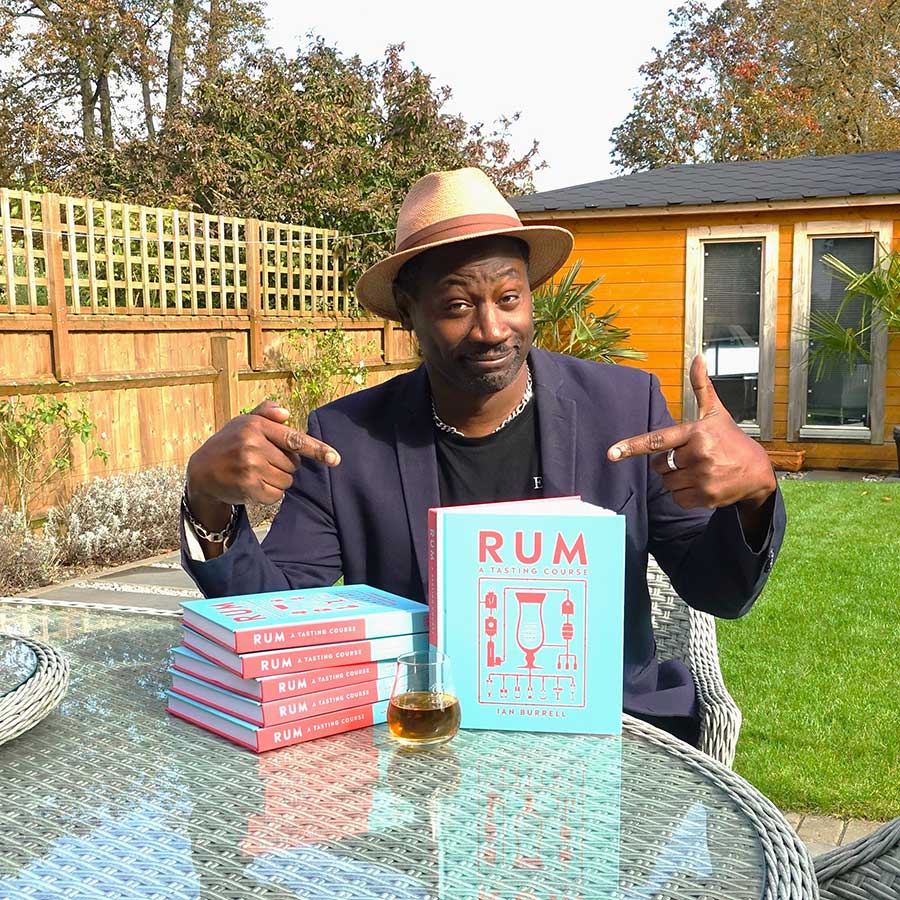

Now let’s talk about Equiano. But before we discuss the current controversy, can you explain how you created your brand? Because I think that’s what every enthusiast dreams of doing one day!

I’ve created many brands for many companies, but as an employee-consultant. I help by coming up with concepts, names, collaborating on the taste aspect… But Equiano was the first time I thought about doing this for myself, creating a brand that I partly owned, to perhaps one day pass on to my children. On Equiano, I worked with three other entrepreneurs to come up with a concept and create a brand.

How did the name come about?

I have always been interested in the story of Equiano, who was enslaved at the age of 12 in Barbados, then travelled to America, England and, finally, at the age of 20, had saved enough money to buy his own freedom. Initially, my former partners wanted to create an African rum. There were a few countries in Africa that produced decent rum, such as Mauritius, the Seychelles and South Africa, but I didn’t think the market was ready for a 100% African rum. And that’s when I came up with the concept of an African and Caribbean rum, because that’s my ethnicity in the UK. No one had ever blended African rum with rum from Barbados before. And it fit perfectly with Equiano’s true story.

How did it work in practice?

I contacted Richard Seale in Barbados, because I think he produces the best rums in the world. And in Mauritius, New Grove, because we also liked their rums. And they said yes straight away. We created the recipe with Richard and it produced a very good rum. Not an elitist rum, but a rum made to be enjoyed by as many people as possible. That’s why we set the alcohol content at 43%. And then, many of my friends invested in the company. They said to me, ‘Ian, you’re creating your own brand, we think it will be a success, we love what you’re doing.’ I received money from the American whisky company Uncle Nearest, but unfortunately they are having problems now. But also from investors, such as Luca Gargano from Velier, and Carsten E. Vlierboom from E&A Scheer…

How did we end up in the current situation where you are in litigation with a former partner and the buyers?

I made a lot of mistakes. One of them was not checking that our trademark had been registered by our company. In fact, from the outset, it was owned by one of the directors we employed as a consultant to set up the company. I thought they would register it under their company and transfer it to ours instead of keeping it. That never happened. And I had no reason to check. In fact, I only realised this last September, when we started having money problems and I was looking for new investors. They said to me, ‘Wait a minute, we can’t invest in your company because you don’t own the trademark.’ It came as a complete surprise!

How did you handle the situation?

I discovered that another director had known about it for six months, but had never told me. She should have informed me well before we ran into financial difficulties and were eventually placed under court administration. When I realised this, I contacted the former partner (Aaisha Dadral), who owned the brand name, to ask her to transfer it to the company. But she did not respond. In the meantime, a new company, run by another director, bought the shares from the receivers. Today, one company owns the assets and the other owns the brand, and they are going to start working together to keep Equiano alive. Except that it is no longer Equiano, nor is it a company owned by someone of African or Caribbean origin, even though they have chosen to use the name.

Will they be able to buy rum from Foursquare and New Grove?

Richard Seale of Foursquare said that he would never sell rum to a company called Equiano if I was no longer involved. So that door is closed. The only place they can buy rum is from the broker E&A Scheer. Will the rum be the same as the liquid we created at Richards Hill? No, because E&A Scheer won’t sell them rum from Barbados. So the product won’t be the same. You also have to take into account the fact that many people bought this rum because of me, my name, my reputation and my connections. However, my business was stolen by one of my partners. This is not well regarded in the rum world, where everything is based on relationships between people. It will be difficult to go to bars and say, ‘We are selling you the rum that Ian created, except that it is no longer the same because Ian is no longer involved.’

What are you going to do now? Launch a new rum?

Actually, I’m launching two new rums! For one of them, the two fathers are Richard Seale and myself. In fact, the recipe will be the same as Equiano, because the liquid was so good, it won so many awards, that it would be crazy not to recreate it. New Grove will also be part of the mix. It will be repackaged and renamed. But there will also be a blend that includes Chamarel, which makes exceptional rums. I’ve always wanted to create a rum with a molasses base and a cane juice base. And then we have another secret project, in partnership with a major record company and a major musical artist. I can’t say too much… except that it’s Jamaican!

Last question, what is your favourite rum?

That’s a difficult question. It’s like asking me what my favourite wine is!

Beaujolais, because I have memories of harvesting grapes there!

OK. For me, it depends on the moment and my mood. But a great Jamaican rum, without too many esters, which I’m not a fan of (I’ll leave that to the Europeans), suits me just fine. Otherwise, I appreciate the fruitiness and balance of a good Barbados rum, such as Foursquare or Mount Gay. When it comes to agricultural rums, it’s hard to choose between Martinique and Guadeloupe! A 12-year-old agricultural rum is fantastic. But I also like white agricultural rums, where you can really taste the terroir, the sugar cane, that kind of thing, with maybe a little lemon and sugar. And if it’s a Jamaican white rum, I’ll take a J. Wray & Nephew. That’s the first one I drank, when I was 4 years old, according to my mother.